Elementary School Homework to Support All Learners

Elementary School Homework to Support All Learners

Elementary School Homework to Support All Learners

As a special education teacher, I often have conversations with parents about homework. Parents want to know: Is homework truly beneficial? Should their child be spending time on assignments after school, or would they be better off focusing on other activities? The answer depends. The appropriateness of homework depends on the individual student, their learning needs, and the way the assignments are structured.

The Case for Homework

Homework, when assigned thoughtfully, should review previously taught classroom material and build important life skills. Here are some of the benefits:

- Enhances Academic Achievement – Research suggests that students who complete homework tend to perform better on standardized tests and classroom assessments. While too much homework may not be beneficial, small amounts of meaningful assignments can help solidify learning.

- Promotes Time Management and Responsibility – Homework teaches students how to manage their time, complete tasks independently, and develop study habits that will serve them well in later grades.

- Facilitates Parental Involvement – Assignments give parents insight into what their child is learning and provide opportunities to engage in their education in a supportive way.

- Reinforces Classroom Learning – Repetition and practice can help young learners build independence of new concepts, like math and reading, where skills build upon one another.

The Challenges of Homework

Despite its benefits, homework is not always appropriate for every student. Here are some common concerns:

- Increases Stress and Burnout – For many young children, particularly those with learning disabilities, homework can be frustrating and overwhelming. Studies have shown that too much homework can lead to stress, anxiety, and a negative attitude toward learning.

- Takes Time Away from Family and Extracurricular Activities – After a full day of learning, children need time to relax, play, and spend quality time with their families.

- Does Not Always Improve Academic Success – Research indicates that for elementary-aged students, the impact of homework on academic achievement is minimal. The key is ensuring that assignments are meaningful rather than just busy work.

- Creates Inequities – Not all students have access to the same resources at home. Some may lack a quiet space to work, parental support, or access to technology, making homework completion more challenging.

Supporting Your Child with Homework

If your child is struggling with homework, there are several ways you can support them and make the process more manageable:

- Create a Homework Routine – Set a regular time and place for homework that minimizes distractions. Being consistent reduces stress.

- Break It Into Chunks – If assignments feel too long, break them into smaller, manageable parts with short breaks in between.

- Encourage Effort, Not Perfection – Praise your child for their hard work and persistence rather than focusing on getting every answer right.

- Communicate with Teachers – If your child is struggling, talk to their teacher. Many teachers are willing to adjust assignments, provide extra support, or suggest alternative ways to reinforce learning at home.

Advocating for Children with Disabilities

For parents of children with learning disabilities or other challenges, homework can be particularly difficult. Here’s how you can advocate for your child:

- Request Accommodations – If your child has an IEP or 504 Plan, discuss whether homework accommodations are needed. This might include extended time, modified assignments, or alternative ways to demonstrate learning.

- Use Assistive Technology – Tools like speech-to-text software, audiobooks, or graphic organizers can make homework more accessible.

- Help Develop Organizational Strategies – Work with your child on using planners, checklists, or timers to help them stay on track.

- Encourage Self-Advocacy – Teach your child to communicate their needs and ask for help when needed.

Policies

My elementary school has a written policy for homework. It serves as a guide for parents but also teachers. Ask your child’s teacher about the school or district homework policy.

As a learning community, my school believes homework is important because it provides students with independent practice and supplemental learning opportunities. It also provides opportunities for parent-school partnerships.

As a split campus (primary and secondary), teachers either assess work weekly or daily. The important thing is that homework can look like different things from unfinished work. In addition to specific assignments, pieces of a project, or something that extends learning from a unit, homework must provide clear and specific directions as to what students need to do.

Everyone has nightly reading homework. Assignments include a good chunk of reading that students must complete nightly. We encourage parents to keep an eye on how much time their child is spending on homework. If their child is struggling too much, parents should reach out to their child’s classroom teacher.

Finding a Balance

Ultimately, homework should support learning without causing too much stress or frustration. Teachers and parents should work together to ensure that assignments are meaningful, accessible, and tailored to individual student needs. If homework becomes a nightly battle, it may be time to rethink the approach. Homework should always mirror what is being taught in the classroom and not waste students’ time.

Homework in elementary school is most effective when it strikes the right balance—reinforcing classroom learning while respecting a child’s need for rest, play, and family time. When assigned, it can build independence, responsibility, and academic skills. Too much or inappropriate homework can lead to frustration and disengagement. The goal should be to create a homework experience that is purposeful, manageable, and supportive of all learners, particularly those with diverse needs.

Writing Standards with Fun Activities (Part 4)

Writing Standards with Fun Activities (Part 4) How to Make Writing Fun (Part 2)

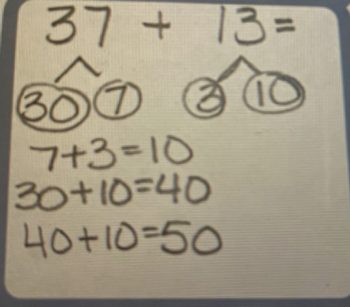

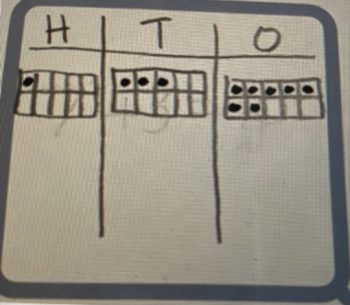

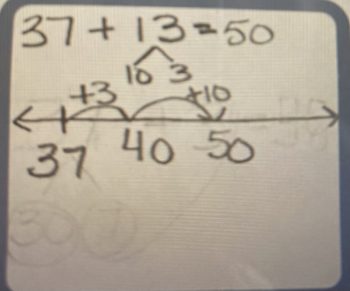

How to Make Writing Fun (Part 2) Let’s Talk Math Strategies

Let’s Talk Math Strategies

Let’s Talk Book Shopping for Children!

Let’s Talk Book Shopping for Children!